BY: ALISON

During my recovery process, I distanced myself from friends, avoided social situations, and became quite isolated. Every time I heard an insensitive comment (albeit without any malicious intent) or felt pressure to meet an unrealistic expectation, I felt more and more unheard, invalidated, and misunderstood. This caused me to feel emotionally unsafe to share honest and detailed accounts of my struggles and experience. The impact of social isolation was especially hard on me, considering my previously extroverted and lively social life.

I went from craving high energy interactions and profound conversations to avoiding eye contact and all forms of communication. However, I was lucky enough to have a few people in my life that knew how to be supportive, what not to say, and how to adjust to the changing dynamics. These people were not only incredibly helpful during my most difficult times, but they made it possible for me to reassimilate to my social life when I felt better.

The following guidelines for how you can be a good friend are based on what my friends did well, what I found effective, and how I’ve supported others through the loss of loved ones, major life changes, and other serious health problems. Keep in mind that everyone needs different types of support and that those needs change circumstantially. So when you’re with someone who’s struggling, don’t hesitate to ask them directly what they want you to say and do

#1. Set your own emotions aside

Empathy allows us to understand and feel other peoples’ physical and emotional pain. Hearing about someone else’s struggles can make us feel uncomfortable, because we become reminded of our own fears and worries. So our initial reaction is to reduce our discomfort by disengaging from what we find upsetting. In conversation, we do this by fidgeting, looking away, or changing the subject. Even statements such as, ‘I’m sure everything will work out’ when used too early in the conversation sends the message, ‘Please stop talking about this.’ That person is then much less likely to speak openly about what’s really going on, even when asked down the line.

After my injury, one particular long term friend asked me about my symptoms, but when I started describing the severe issues, his eyes glazed over, he avoided eye contact, and he froze up. I immediately changed the subject and never answered that question in detail outside of a health professional’s office again.

Disappointingly, even my brief and sugar-coated progress updates triggered similar avoidance reactions in most people. For years, I avoided talking about my injury, feared rejection, felt alone in my suffering, and lost faith in the relationships that I had, all of which had detrimental effects to my confidence. So the next time you’re listening to someone’s problems, brush your own emotions aside and remind yourself that in that moment, it’s not about you

2. Listen actively

To show that you care and that you’re willing to listen to someone’s problems, hear what they have to say, be patient by giving them enough time to finish their thoughts, and acknowledge and respond to what they’ve said using verbal or non-verbal cues (e.g. nodding your head). Then, ask some clarifying or thoughtful questions. Considering how unhappy topics make most people uncomfortable, I could always tell whether someone was genuinely concerned about me and/or interested in learning about brain injury by the number and types of questions that they asked. Finally, end the interaction by making plans for the next call or get together, or by asking the person to update you on any major changes (positive and negative) to their situation. This implies that they can reach out to you if they need to talk to someone and that you want to celebrate their wins with them.

#3. Don’t not do anything

When someone we care about is going through a difficult time, we might feel like we don’t know what to say or do. Out of fear that we might do something wrong, we can end up doing nothing or avoiding interaction with that person altogether.

However, doing nothing makes the person feel like you don’t care, which is probably the furthest thing from the truth. So when you don’t know what to say or do, don’t be afraid to admit that. Say, ‘I am so sorry that this is happening to you. I don’t know what to say, please tell me how I can help.’ I always tell my friends and family to be honest with me if something I’m saying or doing is not helpful, so that I can change my approach and try something else.

Everyone has different needs that change depending on the situation. So be sure to ask, ‘What would be helpful right now?’ and ‘Is this helping? If not, I can try something else.’ Remember, it’s never too late to reach out. A simple, ‘I was thinking about you. How are you doing?’ can mean the world to someone who feels alone in their sadness. Just don’t take it the wrong way if they don’t respond.

#4. Don’t take it personally

Throughout my recovery process, I wanted to be alone but I didn’t want to feel lonely. When I didn’t have the energy or confidence to talk to or see my friends, it made all the difference when they tried to get in touch with me. I loved hearing from people, but I felt too much anxiety and grief to reply. My most helpful friends were the ones that didn’t make me feel guilty for hiding and didn’t give up on me. These special people left voicemails or sent text messages and emails every few weeks to see how I was doing, to offer to visit, or to invite me to their homes for a quiet dinner or get together. Despite my infrequent responses and frequent declined invitations, they never gave up on me and, more importantly, they never took it personally. This reduced my fear of being misunderstood, made me feel genuinely cared for, and let me know that I had good friends to return to when I was ready. Coming out of isolation was one of the most difficult, fear and anxiety-laden aspects of my recovery, but thanks to those friends and their maintained connections, it was easier for me to bounce back and rejoin society as my symptoms subsided. So the next time you check up on someone, don’t wait to hear from them before you get in touch again. Your efforts are more appreciated than you know.

#5. Be considerate

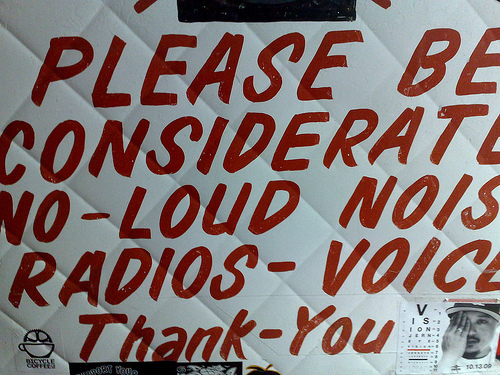

One of my barriers to socializing after a concussion had to do with limitations that healthy people would never think twice about. For example, brightly lit, crowded or noisy places wore me out and made it difficult for me to focus on conversations. Also, driving or traveling by public transit was exhausting, so I had few workable meet-up locations and times. My most understanding friends didn’t always know or understand my barriers, but they always asked. For example, they would suggest an outing and then they would follow it up with, “Would that be okay for you?” They were also willing to offer other suggestions. While hanging out, they would check in and ask me how I was feeling. At their homes, they would say, ‘Let me know if you want to take a nap.’ Those questions sound so simple, yet so few people that I know ever thought to ask them. In social situations, I was hesitant to speak up when I was approaching my limits, but thanks to my friends’ pro-active thoughtfulness and willingness to accommodate, I had fun and I wasn’t made to feel embarrassed while vocalizing my needs.

# 6. Provide long-term support

Whether it’s the death of a loved one, a serious illness such as cancer, or a brain injury, all traumas have long-term, and occasionally, life-long, effects. The more time that passes after a tragedy or accident, the less support that the survivors receive and the less likely they are to ask for help. Just because someone appears to be fully recovered doesn’t mean they are. So, even years after the incident, be sure to check in with them to open a line of communication so that they can get the support that they need.

Alison suffered a concussion in 2013 that completely changed her lifestyle. She is finding her way back to her old self and still loves traveling, dogs, cooking, and helping others. She hopes to help other brain injury survivors and their caregivers by sharing her experience and by spreading awareness.

Filed under: Family, Friendships, relationships Tagged: Friendships

![]()