BY: RICHARD HASKELL

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy? CTE? Say that again? To be sure, outside the medical profession, a term such as this may be daunting. It refers to a progressive and degenerative brain disease that persists over a period of years, not that much different from Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or early onset dementia. It breaks down part of the brain, causing it to deteriorate and lose mass, and in so doing, affects how a person behaves and functions.

Yet unlike other types of cognitive deficiencies, scientists know the root cause of CTE: repeated head trauma.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy was originally termed dementia pugilistica or in layman’s terms, ‘punch drunk.’ It was first noted in boxers during the 1920s who suffered from impaired movement, confusion, speech problems and tremors. (Now dementia pugilistica is recognised as a variant of CTE.) CTE was first documented in medical literature in 1996, and is caused by a number of neurological changes in the brain primarily due to a buildup of an abnormal protein known as tau which serves to stabilize cellular structure in the brain’s neurons. With repeated trauma, the tau becomes defective and begins to congregate in clumps, thereby disrupting the brain’s function.

What are the Symptoms?

It would be difficult to name a contact sport today which doesn’t involve some risk of head injury. Football, hockey, rugby, boxing and even soccer are all sports where players face the possibilities of concussions which can lead to an ABI. But until a few years ago, such injuries were not taken seriously – they were considered ‘just part of the game’ – something to be expected. So what if a player got hit on the head was maybe even knocked out? The prevailing attitude was, “You’ll be fine in a day or two, so now get back on the field, the rink, or the ring and WIN!”

It wasn’t until medical practitioners , not to mention teammates, friends and family of those afflicted began to notice long-term effects such as mood swings, depression and in the worst cases, suicides, that the seriousness of head trauma began to be taken seriously. The clinical symptoms associated with CTE vary in severity, but initial signs may include the following:

- Deterioration in attention, concentration, memory

- Disorientation

- Confusion

- Dizziness

- Headaches

- Lack of insight

- Poor judgment

- Overt dementia

- Slowed muscular movements

- Staggered gait

- Impeded speech

- Tremors

- Vertigo

Currently, medical practitioners believe there are four distinct stages of CTE. During the first stage, an individual may suffer headaches and confusion, but by the time he or she reaches stage two, there may be evidence of social instability, erratic behavior, memory loss, depression and the initial symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. The third stage includes symptoms such as executive function problems, difficulty in judgment, speech difficulties, lack of muscular control and difficulty in swallowing. In the fourth stage, full-blown dementia occurs.

A New Breakthrough

Until a couple of years ago, the only way of testing for CTE was though conducting a postmortem on the brains of the deceased using a microscope to analyze cells.

Nevertheless, a study early in 2013 seems to have finally opened the door to diagnosing CTE in living test subjects. It was headed by Dr. Gary W. Small, an author and professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at UCLA and funded by a $100,000 grant from the Brain Injury Research Institute (BIRA).This non-profit organization in California was founded by neurosurgeon Dr. Julian Bailes and Dr. Julian Bailes, a pathologist who identified the first case of CTE in a former NFL player in 2005.

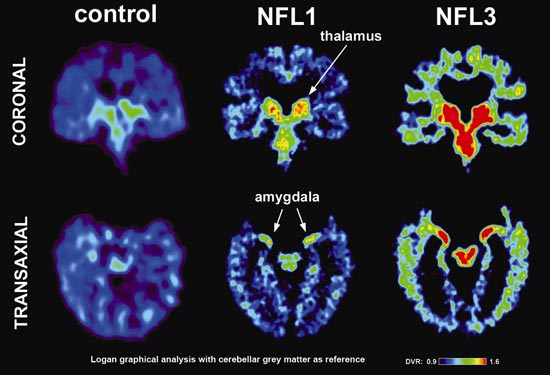

The study was conducted on five patients between the ages of 45 and 73, all of them former NFL players with a history of at least one concussion. It made use of a radioactive biomarker that Small had co-invented for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. In the study, a compound known as FDDNP was injected into a vein where it circulated through the body and attached itself to any tau the brain happened to have and which could be seen by means of a scan. In all five players, the scan ‘lit up’ for tau, particularly in the areas of the brain which control memory and emotions. In addition, the tau patterns were consistent with patterns detected in post-mortems of people diagnosed with CTE. Think of a Geiger-counter!

Small felt that if scientists could begin to diagnose the disease while a patient was still alive, the method of detection could potentially lead to better understanding and treatment for those afflicted while helping to prevent future occurrences.

Dr. Robert Cantu, a senior advisor to the Head, Neck and Spine Committee at the NFL, commented:

“This is the holy grail if it works. This is what we’ve been waiting for, but it looks like it’s probably preliminary to say they’ve got it.”

While autopsy remains the only definitive means of diagnosing CTE, Small’s study has so far proven to be the most promising of several research projects, all of which aim to get inside the skull and seek out potential brain damage before it’s too late.

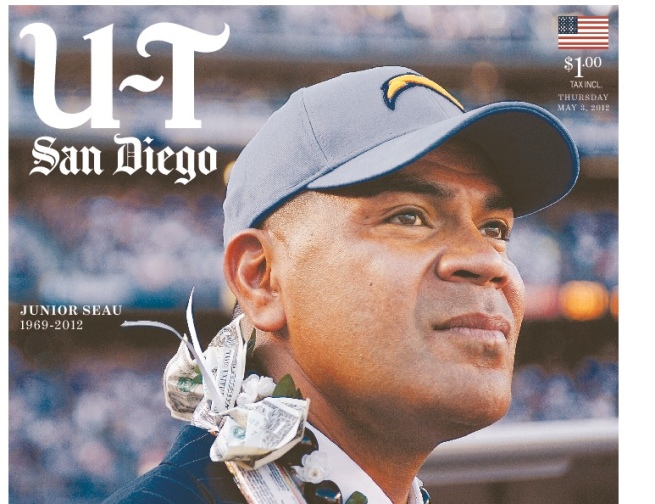

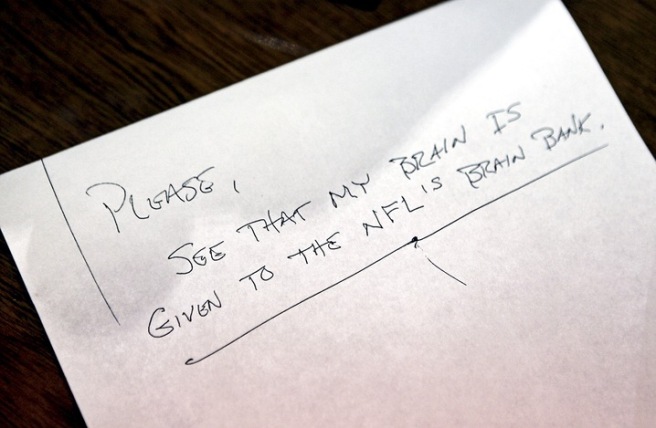

Sadly, it was too late for NFL football defense Dave Duerson and linebacker Junior Seau, both of whom died of self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the chest. Duerson died in February 2011, leaving behind a note requesting his brain be donated to research. Autopsies revealed both players had CTE.

And it seems some players might not want to let others know they have it. In the words of former NHL right-winger Matthew Barnaby:

(Hockey is) a big business and there’s a lot of money involved. We all know as players, we know what management thinks of guys who have had one, two, three concussions, whatever the number may be. Every time you have one more diagnosed, you’re thought of as damaged goods and your price tag when you become a free agent is going to go down. There might not be anyone come calling.

Yet Toronto Maple Leafs goaltender James Reimer feels differently:

This is like that question, ‘Do you want to know right now the day you are going to die?’ It’s not an easy question to answer. But I think the more knowledge you have about your medical situation, the better. It helps you make more informed decisions. If you have a torn ankle, you want to know how badly torn it is. Same with your brain, if it’s damaged, you want to know how bad.

Potentially, athletes who now show signs of CTE could use the information to decide whether or not to retire and when, thus preventing further injury. But according to Bailes, a lot more research is needed before that can happen.

The Future

Concussions are being treated more seriously now than ever before. No longer are they being perceived as a mere ‘bumps on the head.’ And together with this greater awareness is an increase in corporate support.

The NFL’s latest collective bargaining agreement sets aside $100 million to put toward research, much of which is expected to go to brain injury. But so far, only $1 million has been distributed—to Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy.

And the issue of funding is a tricky one. Dr. Charles Bernick of the Cleveland Clinic and one who has undertaken studies on the relation between boxing and brain injuries, explained, “Doing studies like this requires funding, but if you’re heavily indebted in an agency that has a vested interest, there can be a view of a conflict of interest.

Still, it’s a start – and most definitely a step in the right direction. CTE testing on living subjects may well be “the holy grail” with respect to brain injury research, but it will take both time and money before it becomes standard practice.

In the mean time, players who have suffered multiple concussions watch for signs and wait for more research. NFL Super Bowl champ Ben Utecht composed a song ,dedicated to his wife and daughters, about an aging football player who fears he may not remember the names of his family one day due to disease from multiple concussions.

Filed under: CTE Tagged: Ben Utecht, Brain injury, Brain Injury Research Institute, CTE, Dave Duerson, Dr. Charles Bernick, Dr. Gary W. Small, Dr. Julian Bailes, Dr. Robert Cantu, James Reimer, Junior Seau, Matthew Barnaby, NFL, NHL, sports-related injuries, TBI

![]()

Source: BIST Blog